Privacy Examiner Launches Independent Website Risk Detection & Monitoring Service for Healthcare Providers – markets.businessinsider.com

Missed the HIPAA Deadline? Don’t Panic, Health Care Entities Can Still Update Privacy Practices and Policy Notices – JD Supra

Asheville Eye Associates Settles Lawsuit Stemming from DragonForce Ransomware Attack

Asheville Eye Associates, an eye care provider serving patients in Western North Carolina, has agreed to settle class action litigation stemming from a November 2024 cyberattack and data breach.

A cyber threat actor accessed its network and potentially viewed or obtained patient information, including names, addresses, health insurance information, and medical treatment information. The Asheville Eye Associates data breach was reported to the HHS’ Office for Civil Rights as affecting 204,984 individuals. The DragonForce ransomware group took credit for the attack and claimed to have exfiltrated 540 GB of data before encrypting files. The data was leaked when the ransom was not paid. The affected individuals were notified about the attack in early February 2024.

Multiple lawsuits were filed in response to the data breach by plaintiffs Robert Woodsmall, Mimi Reynolds, Dena Brito, Robert Ricchetti, and Christopher Miller. The lawsuits were consolidated, In re Asheville Eye Associates Data Incident Litigation, in South Carolina’s General Court of Justice Superior Court Division. The lawsuit asserted several claims, including negligence, negligence per se, unjust enrichment, breach of implied contract, and breach of confidence. Asheville Eye Associates denies all claims and contentions in the lawsuit and maintains there was no wrongdoing.

Following mediation, all parties agreed to settle the litigation to avoid further litigation costs and expenses, and the uncertainty of a trial. Under the terms of the settlement, Asheville Eye Associates has agreed to pay for attorneys’ fees and expenses, settlement administration and notification costs, service awards for the class representatives, and several benefits for the class members.

Attorneys’ fees and expenses will not exceed $500,000, settlement administration costs are $53,000, and service awards of $1,250 per class representative (total: $6,250) have been approved. Class members may submit a claim for reimbursement of documented, unreimbursed losses due to the data breach up to a maximum of $1,250 per class member. All class members may claim one year of identity theft protection services, and will automatically receive a $10 voucher that can be used toward the purchase of eyeglasses at any Asheville Eye Associates location (except its 21 Medical Park Drive, Asheville, North Carolina location).

The deadline for objection, exclusion, and submitting a claim is April 6, 2026. The final fairness hearing has been scheduled for May 14, 2026.

The post Asheville Eye Associates Settles Lawsuit Stemming from DragonForce Ransomware Attack appeared first on The HIPAA Journal.

January 2026 Healthcare Data Breach Report – The HIPAA Journal

January 2026 Healthcare Data Breach Report

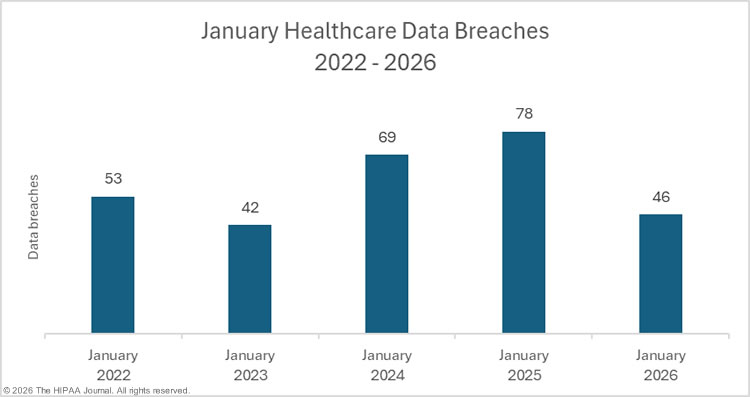

The HHS’ Office for Civil Rights (OCR) healthcare data breach portal shows a slight month-over-month decline in large healthcare data breaches, which fell by 13.2% from December 2025 to 46 data breaches in January 2026.

The OCR breach portal lists healthcare data breaches affecting 500 or more individuals, which have been reported far less frequently during the past 5 months than in the first half of 2025. From September 2025 to January 2026, an average of 46.2 large data breaches were reported to OCR each month, compared to an average of 68.6 breaches per month in the preceding 5 months (April to August). Should this trend continue, 2026 could well see the lowest number of data breaches reported for several years.

We previously suggested that there may be a delay in adding data breaches to the OCR breach portal due to the government shutdown in late 2025, which lasted for 43 days between October 1 and November 12, 2025, during which time no healthcare data breaches were added to the OCR data breach portal. Since we last compiled breach data in January, a further two breaches have been added for October, and 7 data breaches for November. Since relatively few data breaches have been added for those months, it suggests that OCR has largely cleared the backlog of breach reports. The reason for the decline in large data breaches since September 2025 is unclear. Data breaches are also down compared to previous years, with this year’s total being the lowest January total since 2023.

Across the 46 large healthcare data breaches reported in January, the protected health information of 1,441,182 individuals was exposed or impermissibly disclosed. While that represents a 178% increase in affected individuals compared to December 2025, January’s total is well below the 12-month average of 5,107,388 affected individuals per month, and it is the lowest January total since 2020.

In addition to reduced breach numbers, there has also been a reduction in data breach size over the past 5 months. In the 5 months from April 2025 to August 2025, 48.1 million individuals had their health information exposed or impermissibly disclosed in healthcare data breaches. During the following 5 months from September 2025 to January 2026, only 7.2 million individuals had data exposed or impermissibly disclosed, an 85% reduction from the preceding 5 months.

While the reduction in affected individuals is good news, two massive healthcare data breaches occurred last year at business associates of HIPAA-covered entities that are not yet reflected in the OCR breach data. A data breach at Trizetto Provider Solutions last year is now known to have affected at least 3.6 million individuals, and a far worse data breach was experienced by Conduent Business Solutions. According to breach reports to state Attorneys General, at least 25 million individuals were affected by that breach in Oregon and Texas alone. Given the fact that Condusent overrated in many U.S. states, the data breach is likely to have affected many more individuals, and it could rank as one of the top 3 healthcare data breaches of all time.

Biggest Healthcare Data Breaches Reported in January 2026

In January, 11 healthcare data breaches were reported to OCR that affected 10,000 or more individuals. Those 11 data breaches accounted for 92.5% of the affected individuals in January. While data breaches of 10,000 or more records are usually mostly due to hacking and other IT incidents, three of the four largest data breaches of the month were unauthorized access/disclosure incidents, and the top two breaches occurred at state Departments of Human Services.

The largest data breach was reported by the Illinois Department of Human Services, which exposed the protected health information of more than 700K state residents. A website created for internal use to help with resource allocation and decision-making was inadvertently made accessible over the public Internet. The second-largest data breach was reported by the Minnesota Department of Human Services, which affected more than 303K individuals. The breach involved unauthorized access to its MnChoices system, which is used by counties, Tribal Nations, and managed care organizations to support their assessment and planning work for state residents requiring long-term services and support. The system was accessed by a user associated with a licensed healthcare provider, who had no legitimate reason to access the data.

As the table below shows, ransomware groups continue to target the healthcare industry and were behind 6 of the top 11 data breaches in January.

| HIPAA-Regulated Entity | State | Covered Entity Type | Individuals Affected | Data Breach Cause |

| Illinois Department of Human Services | IL | Health Plan | 705,017 | An internal website was inadvertently accessible over the public internet |

| Minnesota Department of Human Services | MN | Health Plan | 303,965 | Unauthorized access to an internal resource by a user associated with a licensed healthcare provider. |

| Clinic Service Corporation | CO | Business Associate | 82,331 | Hacking incident |

| LifeLong Medical Care | CA | Healthcare Provider | 70,000 | Hacking incident at business associate (Trizetto Provider Solutions) |

| Avosina Healthcare Solutions | VA | Business Associate | 44,425 | Ransomware attack (Qilin) |

| Wakefield & Associates, LLC | TN | Business Associate | 31,751 | Ransomware attack (Akira) |

| Jefferson-Blount-St. Clair Mental Health Authority | AL | Healthcare Provider | 30,434 | Ransomware attack (Medusa) |

| Mid Michigan Medical Billing Service, Inc. | MI | Business Associate | 28,185 | Ransomware attack (Qilin) |

| Pecan Tree Dental, PLLC | TX | Healthcare Provider | 13,300 | Ransomware attack (Sinobi) |

| Central Ozarks Medical Center | MO | Healthcare Provider | 11,818 | Hacking incident |

| 360 Dental PC | PA | Healthcare Provider | 11,273 | Ransomware attack |

The HIPAA Breach Notification Rule requires HIPAA-covered entities to report data breaches to the OCR within 60 days of discovery. If the number of affected individuals is not known by the reporting deadline, an estimate of the number of affected individuals should be provided to OCR. It is common for estimates of 500 or 501 affected individuals to be used as placeholders in such cases. In January, three such breaches were reported. The number of affected individuals could be substantially higher for these data breaches.

| Regulated Entity | State | Covered Entity Type | Individuals Affected | Type of Breach |

| Precipio, Inc. | CT | Healthcare Provider | 501 | Hacking/IT Incident |

| Middlesex Sheriff’s Office | MA | Healthcare Provider | 501 | Hacking/IT Incident |

| Central Texas MHMR Center dba Center for Life Resource | TX | Healthcare Provider | 501 | Hacking/IT Incident |

Causes of January 2025 Healthcare Data Breaches

Hacking and other IT incidents continue to dominate the breach reports and were listed as the cause of 36 of the month’s 46 data breaches (78.3%). The protected health information of 343,359 individuals was exposed or stolen in those incidents. Atypically, the number of individuals affected by those incidents was relatively low, as they accounted for just 23.8% of the month’s breach victims. The average breach size was 9,810 individuals, and the median breach size was 3,722 individuals.

While there were only 10 unauthorized access/disclosure incidents in January (21.7%), those incidents accounted for 76.1% of the month’s breach victims. The average breach size was 109,700 individuals, and the median breach size was 3,188 individuals. One loss incident was reported involving the paper records of 821 individuals, but there were no theft or improper disposal incidents. The most common location of breached protected health information in January was network servers (30 incidents), followed by email accounts (8 incidents).

HIPAA-Regulated Entities Affected by Data Breaches

The OCR breach portal data includes 36 data breaches reported by healthcare providers (236,462 affected individuals), 6 data breaches were reported by business associates (190,015 affected individuals), and four data breaches were reported by health plans (1,014,705 affected individuals).

When a data breach occurs at a business associate, it is ultimately the responsibility of each affected HIPAA-covered entity to ensure that the breach is reported in compliance with the HIPAA Breach Notification Rule. Covered entities may delegate the responsibility of reporting the data breach to the business associate, or they may choose to report the breach themselves.

That means that data breaches at business associates are often underrepresented in healthcare data breach reports. The charts below show where the data breaches occurred rather than the reporting entity. As you can see, there is a stark difference this month, as 21 of the month’s data breaches occurred at business associates of HIPAA-covered entities.

Geographical Distribution of Healthcare Data Breaches

In January, HIPAA-regulated entities in 24 U.S. states reported data breaches affecting 500 or more individuals. California topped the list with 8 data breaches, although 7 of those breach reports related to the same incident – The data breach at Trizetto Provider Solutions, which was a business associate or subcontractor of the business associate OCHIN.

| State | Breaches |

| California | 8 |

| Maryland & Texas | 4 |

| Alabama & Indiana | 3 |

| Idaho, Illinois, Michigan, Oregon & Tennessee | 2 |

| Alaska, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, South Carolina & Virginia | 1 |

While California topped the list for data breaches, Illinois and Minnesota were the worst-affected states in terms of affected individuals.

| State | Individuals Affected |

| Illinois | 705,638 |

| Minnesota | 303,965 |

| California | 98,241 |

| Colorado | 82,331 |

| Virginia | 44,425 |

| Alabama | 39,287 |

| Tennessee | 33,092 |

| Michigan | 31,907 |

| Texas | 17,951 |

| Missouri | 11,818 |

| Pennsylvania | 11,273 |

| Idaho | 9,721 |

| New Jersey | 9,526 |

| Maryland | 8,134 |

| Kentucky | 7,990 |

| South Carolina | 7,020 |

| Lopuisiana | 6,530 |

| New York | 4,725 |

| Oregon | 2,781 |

| Indiana | 2,481 |

| Florida | 821 |

| Alaska | 523 |

| Connecticut | 501 |

| Massachusetts | 501 |

HIPAA Enforcement Activity in January 2025

Two enforcement actions were announced in January to resolve alleged violations of the HIPAA Rules. The HHS’ Office for Civil Rights announced a settlement with Top of the World Ranch Treatment Center to resolve an alleged HIPAA Security Rule violation. The behavioral healthcare provider was investigated over a phishing attack that exposed the protected health information of 1,980 individuals.

OCR determined that Top of the World Ranch Treatment Center had not complied with the risk analysis provision of the HIPAA Security Rule, which requires a comprehensive and accurate risk analysis to be conducted to identify risks and vulnerabilities to the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of ePHI. The case was resolved with a $103,000 financial penalty, and Top of the World Ranch Treatment Center agreed to adopt a corrective action plan. This was the 11th HIPAA case to be resolved with a financial penalty under OCR’s risk analysis enforcement initiative.

OCR Director Paula M. Stannard has confirmed that the risk analysis enforcement initiative will continue in 2026 and will be expanded to also cover risk management. The enforcement initiative targeting noncompliance with the HIPAA Right of Access will also continue this year.

The other penalty was imposed following an investigation by the Massachusetts Attorney General, in partnership with the Connecticut Attorney General. Comstar LLC, a Massachusetts-based ambulance billing and collections company, was investigated over a March 2022 cyberattack and data breach that affected 585,621 individuals.

The investigation determined that Comstar had violated the HIPAA Security Rule and the Massachusetts Data Security Regulations by failing to maintain an adequate Written Information Security Program (WISP). The case was resolved with a $515,000 financial penalty, which will be shared between the two states. The settlement also includes several cybersecurity requirements. Comstar had previously settled an OCR HIPAA investigation launched in response to the same data breach and paid a $75,000 financial penalty.

The post January 2026 Healthcare Data Breach Report appeared first on The HIPAA Journal.

Apex Spine & Neurosurgery & North Central Behavioral Health Systems Announce Data Breaches – The HIPAA Journal

Apex Spine & Neurosurgery & North Central Behavioral Health Systems Announce Data Breaches

Data breaches have been announced by Apex Spine & Neurosurgery in Georgia and North Central Behavioral Health Systems in Illinois.

Apex Spine & Neurosurgery

Apex Spine & Neurosurgery in Georgia has notified 2,500 individuals that some of their electronic protected health information has likely been stolen in a ransomware attack. Apex Spine & Neurosurgery said it learned on December 23, 2025, that a cyber threat actor had accessed its network and used ransomware to encrypt files. The forensic investigation confirmed that the cyber actor accessed its network and copied files on December 9, 2025; however, its electronic medical record system was not involved, as it is maintained in a logically separate computer environment.

The stolen files are still being reviewed; however, they contained information such as names, addresses, phone numbers, dates of birth, Social Security numbers, driver’s license numbers, passport numbers, other government identifiers, location of health services, dates of service, treatment or condition information, diagnosis/diagnosis codes, prescription information, history information, assigned physician names; health services payment information, such as financial account number without a security code, access code, or password to access an account, patient account numbers, and health insurance information subscriber or identification numbers. The information copied in the attack varies from individual to individual. Apex Spine & Neurosurgery said it is evaluating further technical safeguards to better protect sensitive data on its network.

The affected individuals have been advised to remain vigilant against identity theft and fraud by monitoring their accounts and explanation of benefits statements for suspicious activity. While the ransomware group was not mentioned in the breach notice, the Interlock ransomware group claimed responsibility for the attack and said 20 GB of data was exfiltrated. Interlock proceeded to leak the stolen data as the ransom was not paid. Apex Spine & Neurosurgery said it was able to securely recover the encrypted data from backups.

North Central Behavioral Health Systems

North Central Behavioral Health Systems, a mental health and substance abuse treatment center with locations in La Salle and Ottawa, Illinois, has identified unauthorized access to an employee’s email account. Suspicious activity was identified in a single email account on or around December 2, 2025. The account was secured to prevent further unauthorized access, and an investigation was launched to determine the nature and scope of the activity.

The investigation confirmed that the breach was limited to a single email account. The account is currently being reviewed to determine the types of information involved and the individuals affected. Notification letters will be mailed to the affected individuals as soon as the review is concluded. Currently, no misuse of patient data has been identified; however, patients have been advised to remain vigilant against data misuse by monitoring their bank accounts and financial statements for suspicious activity. Email security has been enhanced in response to the incident, and complimentary credit monitoring and identity theft protection services are being offered to the affected individuals.

The post Apex Spine & Neurosurgery & North Central Behavioral Health Systems Announce Data Breaches appeared first on The HIPAA Journal.