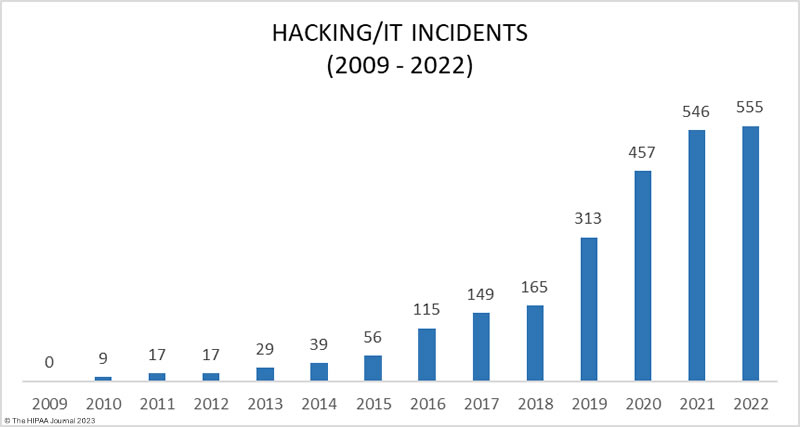

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is transforming the delivery of healthcare in the United States. It is also responsible for one of the biggest threats to the delivery of healthcare in the United States – the theft of healthcare data.

AI has been described as a double-edged sword for the healthcare industry. AI-based systems can analyze huge volumes of data and detect diseases at an early and treatable stage, they can diagnose symptoms faster than any human, and AI is helping with drug development, allowing new life-saving drugs to be identified and brought to market much quicker and at a significantly lower cost. However, AI can also be used by cybercriminals to bypass security defenses and steal healthcare data in greater volumes than ever before – potentially disrupting healthcare operations, affecting health insurance transactions, and preventing patients from receiving timely and effective treatment. This article discusses seven ways AI can be used by hackers to steal healthcare data and suggests ways that healthcare organizations can better prepare for future AI-driven and AI-enhanced attacks.

7 Ways AI Can be Used by Hackers to Steal Healthcare Data

The Increased Threat from AI-Enhanced Phishing Emails

Generative AI models are capable of generating text, images, and other media, and can be used to craft flawless phishing emails that lack the red flags that allow them to be identified as malicious. Security researchers have shown that generative AI is capable of social engineering humans, and AI algorithms can be used to collate vast amounts of personal information about individuals, assisting hackers in crafting highly convincing spear phishing emails.

While this development alone is cause for concern, what is more worrying is AI significantly lowers the bar for conducting phishing campaigns opening. Hackers do not need to be skilled at spear phishing, and AI removes any language constraints. Any bad actor can take advantage of generative AI software to launch spear phishing campaigns at scale to obtain users’ login credentials, deploy malware, and steal healthcare data.

Malicious Emails Written by AI are More Likely to Bypass Email Filters

AI-produced malicious emails are more likely to bypass email filters than malicious emails produced manually. The emails use perfect grammar, lack spelling mistakes, use novel lures, target specific recipients, and are often sent from trusted domains. Combined, this results in a low detection rate by traditional email security gateways and email filters.

AI has also been leveraged to combine obfuscation, text manipulation, and script mixing techniques to create unique emails that are difficult for cybersecurity solutions to identify as malicious. Manually coding these evasive tactics can be a time-consuming process that is prone to error. By leveraging AI, highly evasive email campaigns can be developed in minutes rather than hours.

Most Antivirus Software Cannot Detect Polymorphic Malware

Polymorphic malware is malware that modifies its structure and digital appearance continuously. Traditional antivirus software detects malware based using known virus patterns or signatures and cannot detect this type of threat because polymorphic malware is capable of mutating, rewriting its code, and modifying its signature files.

Polymorphic malware is not specific to AI. Hackers have been programming malware to continuously rewrite its code, and it poses a major challenge for network defenders as it is capable of evading traditional cybersecurity solutions. However, when polymorphic malware is created by AI, code complexity and delivery speed increase – escalating the threat to network security, computer systems, and healthcare data while lowering the entry bar for hackers with limited technical ability.

Brute Force Password Cracking is Quicker with AI

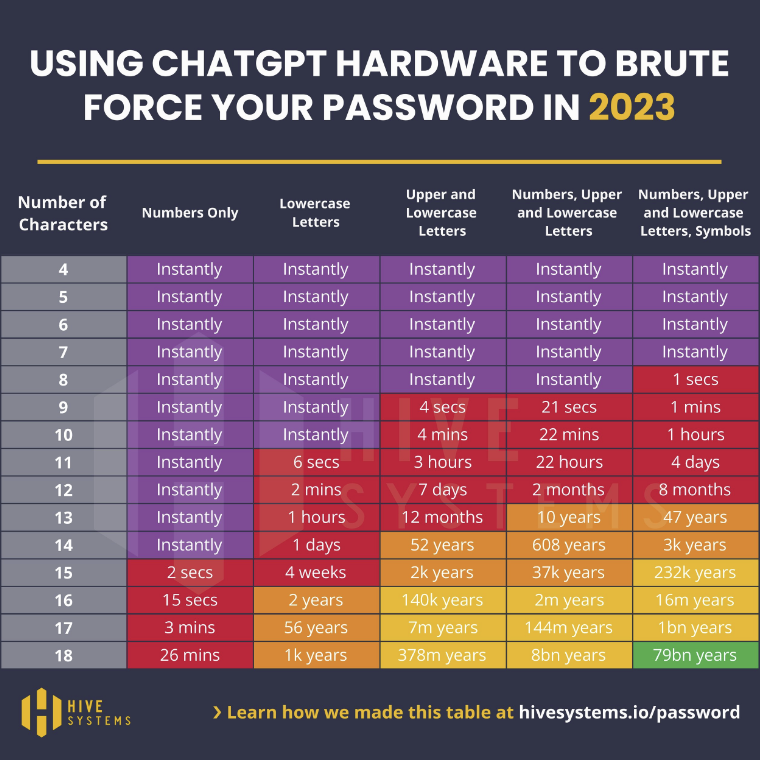

Brute force password cracking is a technique for automating login attempts using all possible character combinations, By using the latest, powerful GPUs, hackers can attempt logins at a rate of thousands of potential passwords per second. In May, we reported on how advances in computer technology were reducing the length of time it takes to crack passwords by brute force and – to demonstrate – published the following Hive Systems table.

Since then, Hive Systems has recalculated these times to demonstrate the potential of using GPUs with AI hardware. It is important to note that these tables compare the times it takes to crack random MD5 hashed passwords. Passwords that include names, dictionary words, sequential characters, commonly used passwords, and recognizable keystroke patterns (i.e., “1qaz2wsx”) will take far less time to crack.

AI Can Find Vulnerabilities and Unprotected Databases Faster

AI-driven software not only analyzes software and systems to predict vulnerabilities before patches are available, but can trawl cybersecurity forums, chat rooms, and other sources to detect vulnerability and hacking trends. The speed at which hackers can move using AI reduces the time security teams have to detect and address vulnerabilities before the vulnerabilities are exploited, from a few weeks to days or even hours.

Additionally, the attack surface has grown considerably in healthcare due to the number of connected devices, providing even more potential targets for breaching internal networks. Hackers can use AI to exploit vulnerabilities in IoT and IoMT devices – or in their connections – to gain access to networks and steal healthcare data. Alternatively, hackers could use AI to manipulate patient data or alter the function of medical devices to target patients.

Hackers can Manipulate Customer Service Chatbots

Conversational AI chatbots (rather than rule-based chatbots) can be manipulated by hackers using a process known as jailbreaking to bypass the chatbot’s guardrails. The process can be used to extract healthcare data from a chatbot on a hospital website or get the chatbot to send healthcare data to the hacker each time the chatbot service is used by a patient.

A similar threat made possible by AI is indirect prompt injection. In this process, adversarial instructions are introduced by a third-party data source such as a web search or API call, rather than directly, which could be via a website or social media post. The injection indirectly alters the behavior of the chatbot to turn it into a social engineer capable of soliciting and stealing sensitive information.

AI Can be Used to Bypass CAPTCHA

CAPTCHA is used by more than 30 million websites to prevent bots from accessing the website, especially malicious bots looking for website vulnerabilities and poorly protected databases. AI-enhanced robotic process automation bots can be trained to learn the source code for CAPTCHA challenges or use optical character recognition to solve the challenges.

CAPTCHA is effective, but can no longer be used to shore up the security of poorly configured websites as AI allows CAPTCHA challenges to be successfully navigated. Thereafter, they can exploit vulnerabilities and steal healthcare data from poorly protected databases, or bombard the server in a DDoS attack to render the website unavailable.

How to Better Prepare for Future Attacks on Healthcare Data

AI can be leveraged by malicious actors to increase the sophistication of their attacks and conduct them in far greater numbers. Legacy defenses and security awareness training will not be enough to prevent employees from interacting with email-borne threats and hackers from infiltrating information systems. Therefore, healthcare organizations and other businesses maintaining healthcare data need to take proactive steps to defend against the malicious use of AI-based systems.

Measures organizations can implement include advanced email filters that support first/infrequent contact safety, mailbox intelligence protection, and zero hour auto purge to retrospectively delete emails if they are weaponized after delivery. If not already implemented, data loss prevention solutions should be considered to protect against hackers using AI to steal healthcare data.

Other ways in which healthcare organizations can prepare for future attacks on healthcare data include supporting existing signature-based antivirus software with extended detection and response solutions, replacing conversational chatbots with rule-based chatbots, and deploying click fraud software that can distinguish between human interactions and bot-driven activity.

One area of preparedness all healthcare organizations should review is password complexity and security. Due to the AI resources available to hackers, it is recommended all passwords are a minimum of fourteen characters in length and contain a random combination of numbers, upper and lower case letters, and symbols. A password manager should be used as it can generate truly random strings of characters for passwords and store them securely in an encrypted password vault.

AI Will Make Cybersecurity More Difficult for the Unprepared

While there are many ways that AI can be used by hackers, AI tools are currently being used to a limited extent by malicious actors but we are already at a stage where it is no longer a case of if these and other novel techniques will be used, but when. Furthermore, because of the ease with which AI generative tools can be used to craft sophisticated phishing emails, write malicious code, and crack passwords, the threshold has been lowered for the skills required to launch attacks on healthcare data.

While many of the measures suggested to prepare for future attacks on healthcare data are likely to incur costs, the alternatives are disruptions to healthcare operations, delayed insurance authorizations, and a fall in the standard of healthcare being provided to patients – notwithstanding that the failure to implement safeguards to protect against these new threats could also result in enforcement action by the HHS’ Office for Civil Rights, Federal Trade Commission, and state Attorneys General.

Steve Alder, Editor-in-Chief, HIPAA Journal

The post Editorial: 7 Ways AI Can be Used by Hackers to Steal Healthcare Data appeared first on HIPAA Journal.

HIPAA compliance laws set the standards for protecting sensitive patient data that healthcare providers, insurance companies, and other covered entities must adhere to. You can use our HIPAA Law Compliance Checklist to

HIPAA compliance laws set the standards for protecting sensitive patient data that healthcare providers, insurance companies, and other covered entities must adhere to. You can use our HIPAA Law Compliance Checklist to