The seven elements of a compliance program are integrated processes organizations can adopt to help develop a culture of compliance in the workplace; and, when applied effectively, the seven elements can also be used to streamline operational processes, optimize organizational performance, and reduce overall costs.

The seven elements of a compliance program are integrated processes organizations can adopt to help develop a culture of compliance in the workplace; and, when applied effectively, the seven elements can also be used to streamline operational processes, optimize organizational performance, and reduce overall costs.

Because HIPAA compliance can be confusing, we have compiled this guide to the seven elements to make them relevant for HIPAA. Some compliance software solutions guide compliance officers through the seven elements as part of their set-up process.

Summary Of The Seven Elements

While the seven elements of a compliance program apply to all industries, they originated in the healthcare industry in the 1990s. This was in response to the growing level of healthcare fraud and abuse and an alleged “compliance disconnect” at the executive level in many hospitals and health systems.

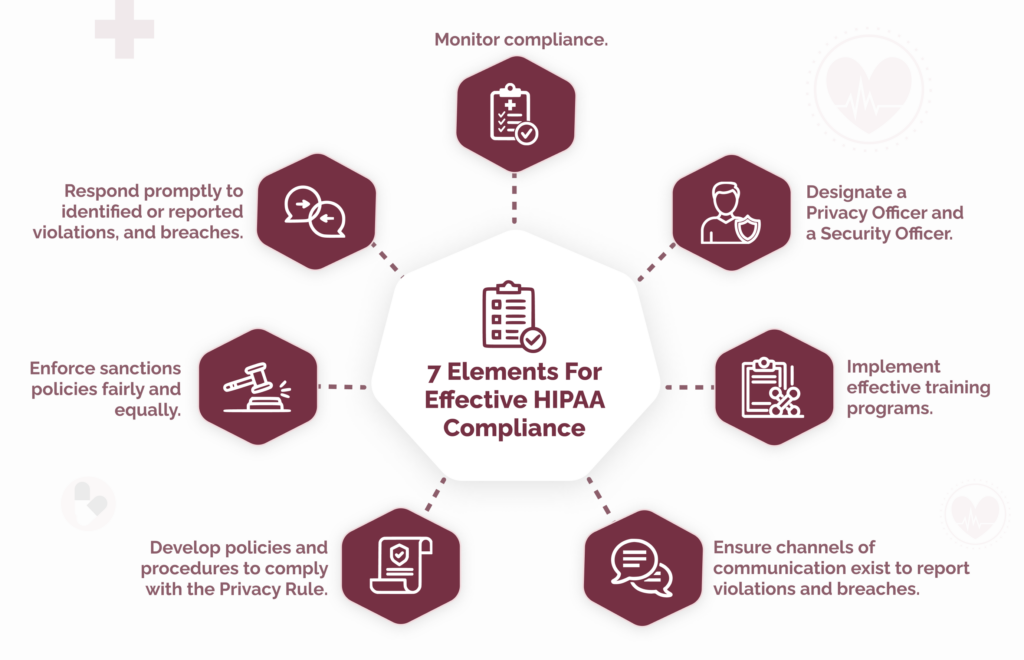

These are the seven elements, which we outline in more detail below:

#1: Implement written policies, procedures, and standards of conduct.

#2: Designate a compliance officer and a compliance committee.

#3: Conduct effective training and education.

#4: Develop effective lines of communication.

#5: Conduct internal monitoring and auditing.

#6: Enforce standards through well-publicized disciplinary guidelines.

#7: Respond promptly to detected offenses and undertake corrective action.

Despite being more than twenty-five years old – and not necessarily having been adopted to tackle the same issues – many organizations still use the seven elements in their original format.

The Background to the Seven Elements

In 1991, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) launched the Workgroup for Electronic Data Interchange (WEDI). WEDI had the objective of reducing administrative costs in the healthcare system by promoting electronic claims submission.

It achieved its objective by requiring insurance carriers to reimburse healthcare providers more quickly for electronic claims than for paper claims, thus encouraging providers to submit more claims electronically.

As a result, the percentage of claims submitted electronically over the next five years more than doubled – making it harder for adjudicators to identify fraud and abuse attributable to unbundling, duplication, and global service violations.

According to a Congressional Report published by the General Accounting Office in 1995, it was estimated that as much as 10 percent of national healthcare spending was attributable to waste, fraud, and abuse (around $98 billion at the time).

The following year, the long-running Caremark Derivative Litigation case concluded – a case in which it was claimed the company’s board of directors had failed in their fiduciary duty of care to ensure the company’s compliance program was enforced.

Although cleared of “lacking good faith in the exercise of monitoring duties or conscientiously permitting a known violation to occur”, the company settled multiple felony charges against it by paying $250 million in civil and criminal fines.

The relevance of this case is that Caremark’s primary operations were providing patient care and managed care services; and, although the company had implemented compliance policies to prevent breaches of Anti-Referral Payments Laws, a series of violations resulted in shareholders claiming the board of directors had failed to adequately enforce the policies and, as a result, exposed the company to regulatory fines.

This accusation was not lost on the HHS’ Office of Inspector General (OIG).

OIG Publishes First Model Compliance Plan

The year after the conclusion of the Caremark Derivative Litigation case, OIG published its first model compliance plan (62 FR 9435-9441). Although aimed at clinical laboratories, the model compliance plan consisted of seven “compliance plan elements” that subsequently evolved into “the seven fundamental elements of an effective compliance program” in later compliance plans for hospitals, home health agencies, hospices, and nursing facilities.

The primary objective of the plan is fairly transparent. In the preamble to each of the plans, OIG states “many providers and provider organizations have expressed an interest in better protecting their operations from fraud and abuse through the adoption of voluntary compliance programs.” The word “fraud” is repeated a further twenty-eight times in the compliance plan for hospitals (63 FR 8987) and the compliance plan for nursing facilities (65 FR 14289).

It is also noticeable that, from the second plan onward, each plan includes a footnote stating “recent case law suggests that the failure of a corporate Director to attempt in good faith to institute a compliance program in certain situations may be a breach of a Director’s fiduciary obligations” – referencing the Caremark Derivative Litigation case. Clearly, OIG wanted to send the message that, if a voluntary compliance plan was implemented, oversight of the plan was expected.

The biggest influence for the creation of the seven elements of a compliance program (fraud prevention) is sometimes overlooked. This is not necessarily a bad thing because – around the same time – the passage of HIPAA introduced fraud controls and transaction standards that made it harder for healthcare providers to defraud or abuse the system. However, the seven elements can be adapted for more positive purposes than preventing, detecting, and responding to fraud.

What are the Seven Elements of a Compliance Program?

Since the first appearance of the seven elements, some versions have been amended or extended to meet organizational or regulatory requirements.

Since the first appearance of the seven elements, some versions have been amended or extended to meet organizational or regulatory requirements.

For example, when the Affordable Care Act made a compliance program a requirement of Medicare participation for some healthcare providers (42 CFR §483.85), an element was added that prohibits organizations from delegating discretionary authority to individuals who “the organization knew, or should have known through the exercise of due diligence, had the propensity to engage in criminal, civil, and administrative violations of the Social Security Act.”

However, as mentioned in the introduction to this article, many organizations that have implemented a compliance plan voluntarily still use the seven elements of a compliance program in their original format.

Please use the form on this page to arrange to receive a free copy of the HIPAA Compliance Checklist to use with the seven elements of a compliance program.

#1 Implement written policies, procedures, and standards of conduct

The seven elements of a compliance program are often depicted as a linear “start-to-finish” program or as a wheel that starts revolving again when it is completed its first cycle. Neither depiction is entirely accurate, as the seven elements of a compliance program have to integrate with each other at all times to make the program work effectively and facilitate improvements to the program.

The seven elements of a compliance program are often depicted as a linear “start-to-finish” program or as a wheel that starts revolving again when it is completed its first cycle. Neither depiction is entirely accurate, as the seven elements of a compliance program have to integrate with each other at all times to make the program work effectively and facilitate improvements to the program.

The first of the seven elements of a compliance program is a suitable example of why it is important to view a compliance program holistically because it calls for the development of standards (etc.) under the direction of a compliance officer. Yet organizations are not advised to designate a compliance office until element #2:

“Every compliance program should develop and distribute written compliance standards, procedures, and practices that guide the facility and the conduct of its employees throughout day-to-day operations. These policies and procedures should be developed under the direction and supervision of the compliance officer, the compliance committee, and operational managers.”

If you view the seven elements of a compliance program as a linear program, you could be confused when the second element instructs you to designate the compliance officer you need to complete the first element. You might also be confused if you view the compliance program as a wheel, because it means you will need to rotate the wheel counter clockwise from #2 to #1.

#2 Designate a compliance officer and compliance committee

The temptation with element #2 is to delegate the role of compliance officer and the membership of a compliance committee to members of the same HR, legal, or operations teams or department heads of these teams. This can be a mistake if (for example) the legal team does not understand the real-life challenges of compliance in the workplace.

While it is a good idea to head the compliance committee with a person of authority, it is beneficial to include personnel with public-facing roles (i.e., healthcare professionals) and a mixture of personnel from IT, security, and administration who can provide insights on which policies will work and which won’t without changes to working practices.

#3 Conduct effective training and education

Integrating training and education into a compliance program should not be difficult for most organizations in the healthcare industry, as the majority are required to comply with the HIPAA training requirements, while some are also required to provide annual compliance training as a condition of participation in the Medicare program.

Of significance, in the original seven elements of a compliance program, OIG notes that the continual retraining of personnel at all levels (emphasis added) is a significant element of an effective compliance training program. Along the same lines, OIG adds that adherence to the elements of the compliance program should be a factor in evaluating the performance of managers and supervisors.

#4 Develop effective lines of communication

The development of effective lines of communication is pivotal to the seven elements of a compliance program because effective lines of communication are necessary for members of the workforce to raise questions, report violations, and provide feedback on corrective action plans that may necessitate amendments to policies and procedures and further training.

Ideally the creation and maintenance of effective lines of communication between the compliance officer/committee and the workforce should include a hotline or anonymous reporting system to receive questions, reports, and feedback. Organizations should also adopt procedures to protect the anonymity of complainants and to protect whistle-blowers from retaliation.

#5 Conduct internal monitoring and auditing

This element of an effective compliance program provides an opportunity for executive officers to demonstrate oversight by requesting compliance reports and audits from the compliance officer. In healthcare environments, these reports and audits should be conducted regularly to comply with the HIPAA requirement for regular risk analyses and be available at all times for executive review.

If executive officers participate in this element, it also provides an opportunity to extend lines of communication “from the top to the bottom”. Although it is not always practical to have members of the workforce communicate directly with executive officers (and vice versa), the involvement of executive officers demonstrates a commitment to compliance throughout the entire organization.

#6 Enforce standards through well-publicized disciplinary guidelines

Most organizations distribute disciplinary guidelines at the point of training. Indeed, in the healthcare industry, the standards relating to training and sanctions are almost adjacent to the Administrative Requirements of the Privacy Rule – so it is rare that an explanation of the organization’s sanctions policy is not included in initial HIPAA training.

With regard to enforcing standards, it is important that sanctions are applied fairly. If one group of the workforce is sanctioned more often or more harshly than another group for no justifiable reason, executive officers need to find out why. While it may be the case that one manager is enforcing standards over-zealously, it may equally be the case that another manager is allowing the workforce to take shortcuts with compliance “to get the job done”.

#7 Respond promptly to detected offenses and undertake corrective action

When the seven elements of a compliance plan were originally published in the 1990s, this element focused almost entirely on detecting fraud, reporting it, and enforcing sanctions or implementing measures to prevent it from happening again. With fraud prevention being a less important objective of a compliance plan than it was twenty-five years ago, this element can be used to monitor the effectiveness of the compliance program and improve it where necessary.

For example, if an offense has occurred due to a loophole in a policy (element #1), a lack of training (#3), a communication failure (#4), or a monitoring issue (#5), the compliance officer (#2) can evaluate the existing policies, procedures, and standards, and adjust them as necessary (#7). If the offense has occurred due to the actions of a non-compliant member of the workforce, it may be necessary to increase the penalties in the sanctions policy (#6) to be more of a deterrent.

The Challenges and Benefits of Adopting a Compliance Plan

Adopting the seven elements of a compliance plan can be challenging for an organization starting from scratch. It can be difficult to get leadership buy-in because compliance is not perceived as a revenue generator, it can be difficult to define compliance roles in a complex regulatory environment, and it can be difficult to pull everything together with limited resources.

Adopting the seven elements of a compliance plan can be challenging for an organization starting from scratch. It can be difficult to get leadership buy-in because compliance is not perceived as a revenue generator, it can be difficult to define compliance roles in a complex regulatory environment, and it can be difficult to pull everything together with limited resources.

In healthcare environments, these challenges are mitigated by the fact that many of the elements are – or should be – already in place. HIPAA-covered entities should have developed policies and procedures to comply with the Privacy Rule, have a training and sanctions program up and running, and have procedures for conducting internal audits and responding to data breaches.

All that needs to be done in many healthcare environments is for the compliance officer to bring together the seven elements of a compliance plan into one integrated plan. When managed effectively, the plan will help organizations develop a culture of compliance that can help to reduce costs (i.e., regulatory fines), enhance the organization’s operations (i.e., through improved communication), and advance the quality of healthcare.

This final benefit of adopting a compliance plan is one many organizations are only starting to realize as it has only recently been demonstrated that, when patients believe PHI will remain confidential, they tend to be more forthcoming about healthcare issues. This enables healthcare professionals to make better-informed diagnoses and prescribe more effective courses of treatment, which results in better patient outcomes, satisfaction scores, workplace morale, and staff retention.

Get Help Developing Your Compliance Plan

Multiple sources on the Internet offer help with developing a compliance plan. One of the best is the HHS’ Office of Inspector General compliance guidance web page which includes updated guidance on the seven elements of a compliance program in its General Compliance Program Guidance document.

However, if your organization is a multi-disciplined Covered Entity or Business Associate, and you need more granular help developing a compliance plan, it may be worthwhile reviewing our HIPAA compliance checklist.

Steve Alder, Editor-in-Chief, The HIPAA Journal

The post Seven Elements Of A Compliance Program appeared first on The HIPAA Journal.

Since the first appearance of the seven elements, some versions have been amended or extended to meet organizational or regulatory requirements.

Since the first appearance of the seven elements, some versions have been amended or extended to meet organizational or regulatory requirements.

Adopting the seven elements of a compliance plan can be challenging for an organization starting from scratch. It can be difficult to get leadership buy-in because compliance is not perceived as a revenue generator, it can be difficult to define compliance roles in a complex regulatory environment, and it can be difficult to pull everything together with limited resources.

Adopting the seven elements of a compliance plan can be challenging for an organization starting from scratch. It can be difficult to get leadership buy-in because compliance is not perceived as a revenue generator, it can be difficult to define compliance roles in a complex regulatory environment, and it can be difficult to pull everything together with limited resources.