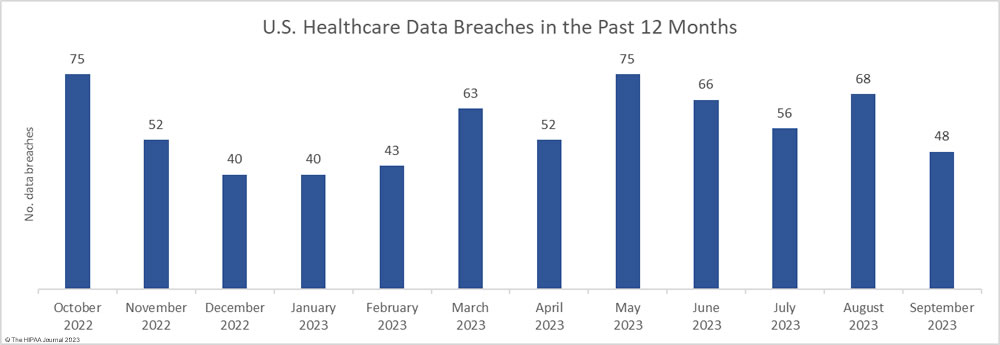

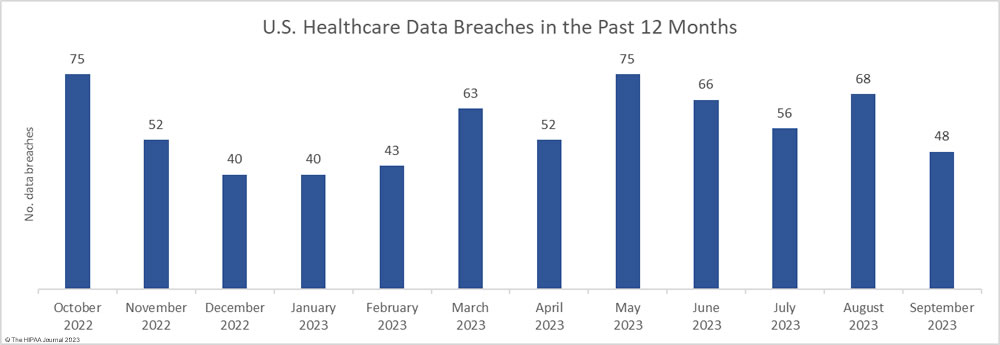

September was a much better month for healthcare data privacy, with the lowest number of reported healthcare data breaches since February 2023. In September, 48 data breaches of 500 or more records were reported to the HHS’ Office for Civil Rights (OCR), which is well below the 12-month average of 57 data breaches a month.

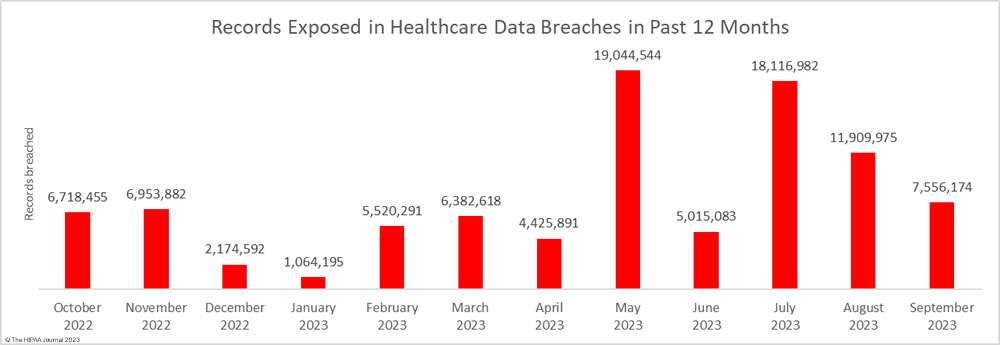

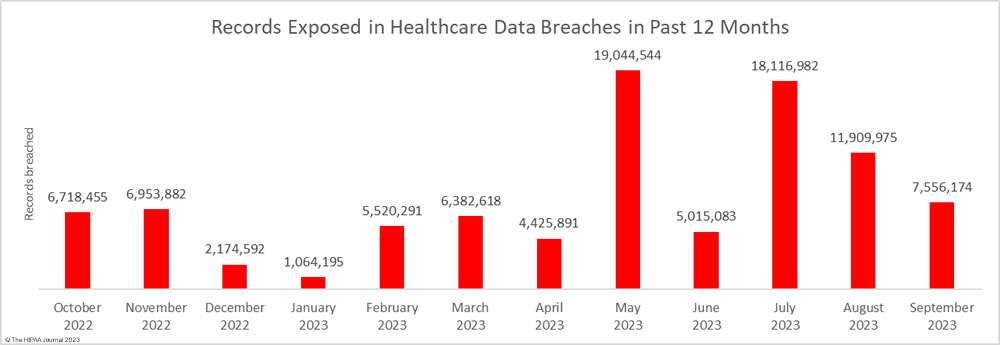

For the second successive month, there was a fall in the number of breached records, which dropped 36.6% month-over-month. Across the 48 reported data breaches, the protected health information of 7,556,174 individuals was exposed or impermissibly disclosed. September’s total was below the 12-month average of 7,906,890 records per month, but this year has seen two particularly bad months for data breaches. More healthcare records were exposed in May and June than were exposed in all of 2020!

The high number of breached records can partly be attributed to the mass exploitation of a zero-day vulnerability in Progress Software’s MOVEit solution, which is used by healthcare organizations and their business associates for transferring files. According to Emsisoft, which has been tracking the MOVEit data breaches, 2,553 organizations were affected by the attacks globally, and 19.2% of those were in the health sector. Most of these breaches are now believed to have been reported.

Largest Healthcare Data Breaches in September 2023

There were 16 data breaches reported in September that involved 10,000 or more records, four of which – including the largest data breach of the month – were due to the mass exploitation of the vulnerability that affected the MOVEit Transfer and MOVEit Cloud solutions (CVE-2023-34362). The healthcare industry continues to be targeted by ransomware and extortion gangs, including Clop, Rhysida, Money Message, NoEscape, Karakurt, Royal, and ALPHV (BlackCat). Three of the 10,000+ record data breaches were confirmed as ransomware attacks, although several more are likely to have involved ransomware or extortion. It is common for HIPAA-covered entities not to disclose details of hacking incidents.

While hacking incidents often dominate the headlines, the healthcare industry suffers more insider breaches than other sectors, and September saw a major insider breach at a business associate. An employee of the business associate Maximus was discovered to have emailed the protected health information of 1,229,333 health plan members to a personal email account.

| Name of Covered Entity |

State |

Covered Entity Type |

Individuals Affected |

Type of Breach |

Cause of Breach |

| Arietis Health, LLC |

FL |

Business Associate |

1,975,066 |

Hacking/IT Incident |

MOVEit Hack (Clop) |

| Virginia Dept. of Medical Assistance Services |

VA |

Health Plan |

1,229,333 |

Hacking/IT Incident |

Employee of a business associate (Maximus) emailed documents to a personal email account |

| Nuance Communications, Inc. |

MA |

Business Associate |

1,225,054 |

Hacking/IT Incident |

MOVEit Hack (Clop) |

| International Business Machines Corporation |

NY |

Business Associate |

630,755 |

Unauthorized Access/Disclosure |

MOVEit Hack (Clop) |

| Temple University Health System, Inc. |

PA |

Healthcare Provider |

430,381 |

Hacking/IT Incident |

Hacking incident at business associate (no information released) |

| Prospect Medical Holdings, Inc. |

CA |

Business Associate |

342,376 |

Hacking/IT Incident |

Rhysida ransomware attack |

| United Healthcare Services, Inc. Single Affiliated Covered Entity |

CT |

Health Plan |

315,915 |

Unauthorized Access/Disclosure |

MOVEit Hack (Clop) |

| Oak Valley Hospital District |

CA |

Healthcare Provider |

283,629 |

Hacking/IT Incident |

Hacked network server |

| Bienville Orthopaedic Specialists LLC |

MS |

Healthcare Provider |

242,986 |

Hacking/IT Incident |

Hacked network server (data theft confirmed) |

| Amerita |

KS |

Healthcare Provider |

219,707 |

Hacking/IT Incident |

Ransomware attack on parent company (PharMerica) by Money Message group |

| Community First Medical Center |

IL |

Healthcare Provider |

216,047 |

Hacking/IT Incident |

Hacked network server |

| OrthoAlaska, LLC |

AK |

Healthcare Provider |

176,203 |

Hacking/IT Incident |

Hacking incident (no information released) |

| Acadia Health, LLC d/b/a Just Kids Dental |

AL |

Healthcare Provider |

129,463 |

Hacking/IT Incident |

Ransomware attack – Threat group confirmed data deletion |

| Founder Project Rx, Inc. |

TX |

Healthcare Provider |

30,836 |

Hacking/IT Incident |

Unauthorized access to email account |

| Health First, Inc. |

FL |

Healthcare Provider |

14,171 |

Hacking/IT Incident |

Unauthorized access to email account |

| MedMinder Systems, Inc. |

MA |

Healthcare Provider |

12,146 |

Hacking/IT Incident |

Hacked network server |

Data Breach Types and Data Locations

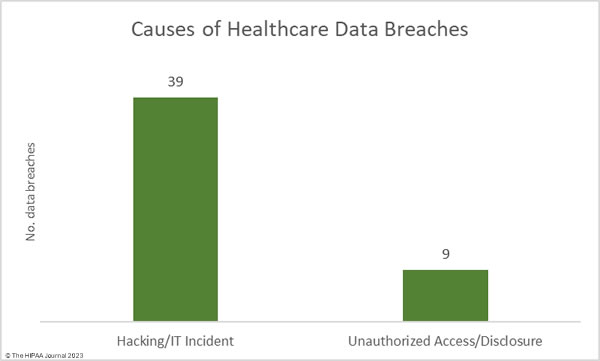

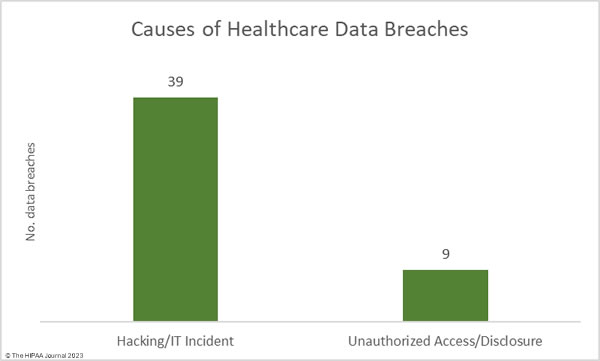

Hacking and other IT incidents continue to dominate the breach reports. In September, hacking/IT incidents accounted for 81.25% of all reported data breaches of 500 or more records (39 incidents) and 87.23% of the exposed or stolen records (6,591,496 records). The average data breach size was 169,013 records and the median data breach size was 4,194 records.

There were 9 data breaches classified as unauthorized access/disclosure incidents, across which 964,678 records were impermissibly accessed by or disclosed to unauthorized individuals. The average data breach size was 107,186 records and the median breach size was 2,834 records.

There were no reported incidents involving the loss or theft of paper records or electronic devices containing ePHI, and no reported incidents involving the improper disposal of PHI.

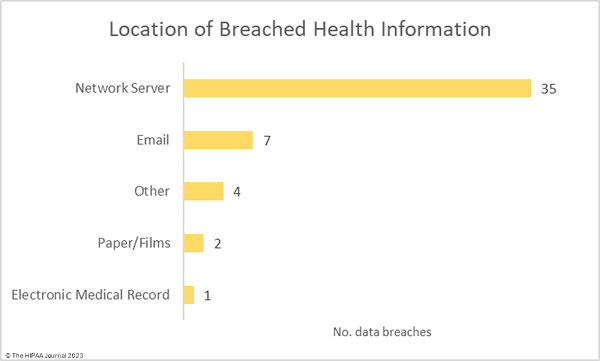

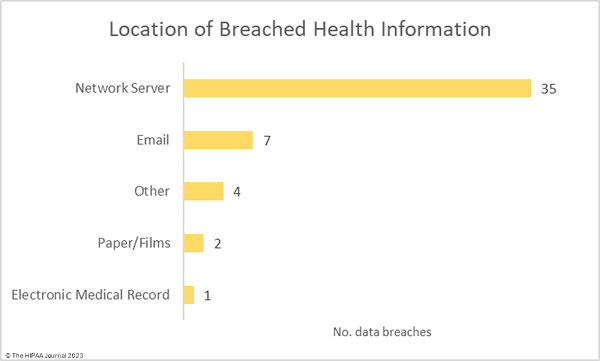

Given the large number of hacking incidents, it is no surprise that network servers were the most common location of breached protected health information. 7 incidents involved unauthorized access to email accounts.

Where did the Data Breaches Occur?

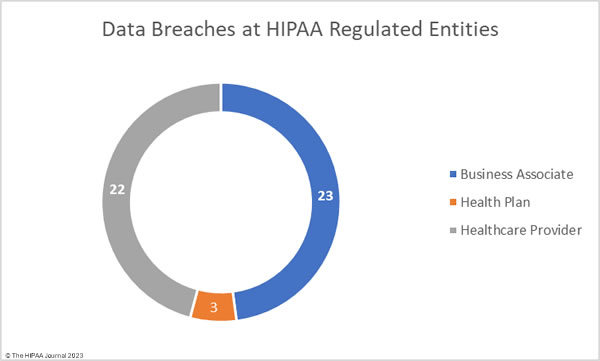

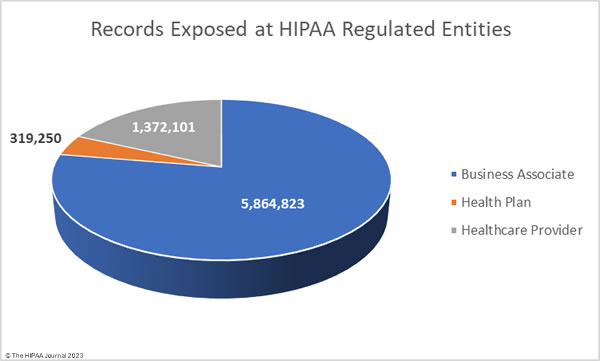

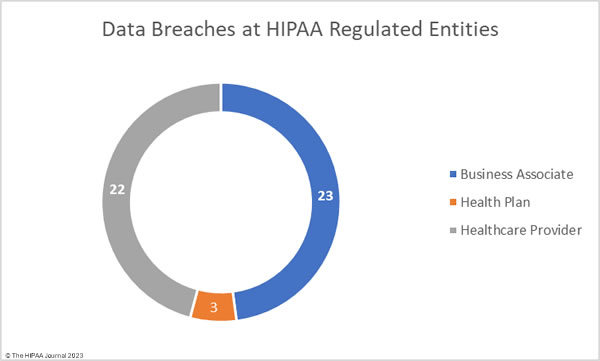

The raw data from the OCR data breach portal shows healthcare providers were the worst affected entity in September, with 30 healthcare providers reporting data breaches. There were 11 data breaches reported by business associates and 7 breaches reported by health plans. These figures do not tell the full story, as the reporting entity may not be the entity that suffered a data breach. Many data breaches occur at business associates of HIPAA-covered entities but are reported to OCR by the covered entity rather than the business associate.

To better reflect this and to avoid the underrepresentation of business associates in the healthcare data breach statistics, the charts below show where the data breaches occurred rather than the entity that reported the data breach.

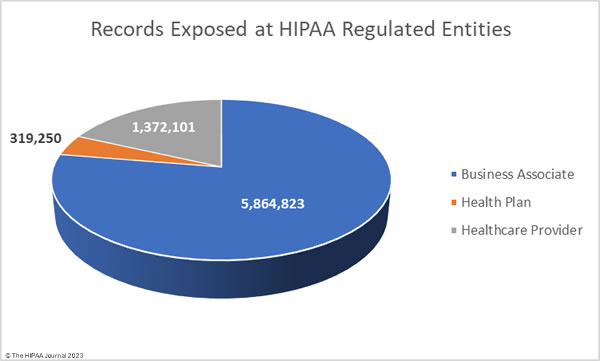

Business associate data breaches are often severe as if a hacker gains access to the network of a business associate, they can access the data of all clients of that business associate. In September the average size of a business associate data breach was 5,864,823 records (median: 2,729 records). The average size of a healthcare provider data breach was 1,372,101 records (median: 7,267 records), and the average health plan data breach involved 319,250 records (median: 2,834 records).

Geographical Distribution of Data Breaches

Healthcare data breaches of 500 or more records were reported by HPAA-regulated entities in 24 states. California, Florida, and New York were the worst affected states with 4 breaches each.

| State |

Breaches |

| California, Florida & New York |

4 |

| Georgia, Illinois & Texas |

3 |

| Alabama, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, New Jersey, Pennsylvania & Virginia |

2 |

| Arizona, Arkansas, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Nevada, North Carolina & Tennessee |

1 |

HIPAA Enforcement Activity in September 2023

All healthcare data breaches of 500 or more records are investigated by OCR to determine whether they were the result of non-compliance with the HIPAA Rules. OCR has a backlog of investigations due to budgetary constraints, and HIPAA violation cases can take some time to be resolved. In September, OCR announced that one investigation had concluded and a settlement had been reached. The case dates back to March 2014, when an online media source reported that members of the health plan were able to access the PHI of other members via its online member portal. The breach was reported to OCR as affecting fewer than 500 plan members and OCR launched a compliance review in February 2016. Three years later, another breach was reported – a mailing error, this time affecting 1,498 plan members.

OCR investigated LA Care Health Plan again and found multiple violations of the HIPAA Rules – A risk analysis failure, insufficient security measures, insufficient reviews of records of information system activity, insufficient evaluations in response to environmental/operational changes, insufficient recording and examination of activity in information systems, and an impermissible disclosure of the ePHI of 1,498 individuals. The case was settled, and LA Care Health Plan agreed to adopt a corrective action plan and pay a $1,300,000 penalty.

State attorneys general are also authorized to investigate healthcare data breaches and fine organizations for HIPAA violations. From 2019 to 2022, there were relatively few financial penalties imposed for HIPAA violations or equivalent violations of state laws, but there has been a significant increase in enforcement actions in 2023. Between 2019 and 2022 there were 12 enforcement actions by state attorneys general that resulted in financial penalties. 11 penalties have been imposed so far in 2023.

In September, three settlements were announced by state attorneys general. The first, and the largest, was in California, which fined Kaiser Foundation Health Plan Foundation Inc. and Kaiser Foundation Hospitals $49 million. Kaiser was found to have violated state laws by improperly disposing of hazardous waste and violating HIPAA and state laws by disposing of protected health information in regular trash bins.

The Indiana Attorney General announced that a settlement had been reached with Schneck Medical Center following an investigation of a data breach involving the PHI of 89,707 Indiana residents. The settlement resolved alleged violations of violations of the HIPAA Privacy, Security, and Breach Notification Rules, the Indiana Disclosure of Security Breach Act, and the Indiana Deceptive Consumer Sales Act. Schneck Medical Center paid a $250,000 penalty and agreed to improve its security practices.

The Colorado Attorney General announced that a settlement had been reached with Broomfield Skilled Nursing and Rehabilitation Center over a breach of the protected health information of 677 residents. The settlement resolved alleged violations of HIPAA data encryption requirements, state data protection laws, and deceptive trading practices. A penalty of $60,000 was paid to resolve the alleged violations, with $25,000 suspended, provided corrective measures are implemented.

The post September 2023 Healthcare Data Breach Report appeared first on HIPAA Journal.